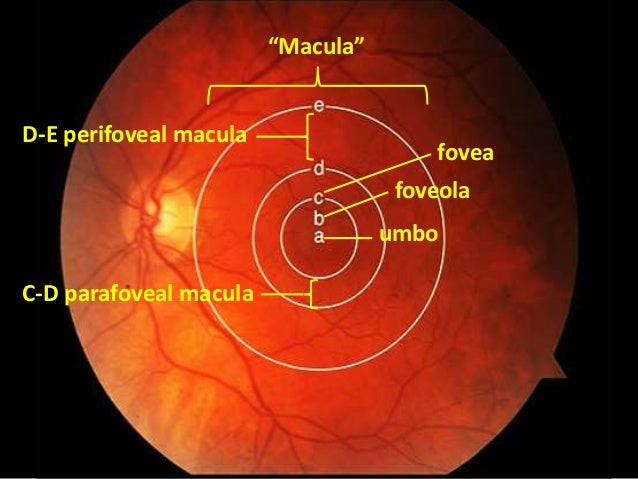

PVD is characterized by a separation between the posterior vitreous cortex and the internal limiting membrane (ILM) of the retina as a result of a normal physiologic process that occurs invariably with age. In order to better understand vitreoretinal interface disorders, it is first essential to comprehend the normal sequence of events during the evolution of PVD. The recognition of the role of VMT in these macular abnormalities is imperative for diagnosis and appropriate management of affected patients. 8, 10- 15 Although the pathogenesis of these disorders is not completely understood, 7, 9 OCT has implicated tractional forces as a plausible cause. It remains unclear why patients with VMT have distinct maculopathies a question that like many others is the focus of several recently published studies. Nowadays, VMT is believed to be associated with a broad spectrum of maculopathies, including cystoid macular edema (CME), epiretinal membrane (ERM), and macular hole (MH) formation, all attributed to a common etiology.

5- 7Īmong vitreoretinal interface abnormalities, VMT syndrome is probably one of the conditions which has been significantly improved in terms of pathophysiologic concepts. Spectral domain high definition OCT (HD-OCT) has provided new insight into the understanding of VMT syndrome by providing better evaluation of tractional forces at the vitreoretinal interface, as well as comprehending its relationship with particular macular conditions. In the classic form of VMT syndrome, as initially described 1, the vitreous is separated from the retina throughout the peripheral fundus but remains adherent posteriorly, engendering anteroposterior traction on a broad, often dumbbell-shaped region encompassing the macular area and optic nerve several disc areas in size. VMT was assumed to be an uncommon entity and not associated with other macular disorders. Hence, the term vitreomacular traction (VMT) syndrome was coined. This condition was confirmed, not by imaging studies, such as optical coherence tomography (OCT) which was not available at that time, but through the use of histological studies.

In 1970, Reese et al 1 described an unusual macular condition in which an incomplete posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) exerted traction on the macula and was accompanied by decreased visual acuity (VA). Surgical procedures are effective to relieve VMT and improve VA in most eyes outcomes vary with VMT morphology and the duration of symptoms. Despite similar postoperative visual acuity (VA) in focal and broad VMT subgroups, visual improvement is greater with focal VMT because preoperative VA is frequently lower. Focal VMT usually leads to macular hole formation, tractional cystoid macular edema and foveal retinal detachment, while broad VMT is associated with epiretinal membranes, diffuse retinal thickening and impaired foveal depression recovery. The size and severity of the remaining vitreomacular attachment may define the specific maculopathy. These macular changes are closely related to the VMT configuration and have led to proposing classification of this syndrome based on OCT findings. VMT syndrome is implicated in the pathophysiology of a number of macular disorders, translating into a variety of anatomical and functional consequences underscoring the complexity of the condition. While technological advances drive us into the future by clarifying the pathophysiology of many diseases and enabling novel therapeutic options, it is at the same time necessary to review basic disease concepts in addition to definitions and classifications. The advent of new technologies such as high definition optical coherence tomography (OCT) has not only provided unprecedented imaging capabilities, but also raised the need to define concepts not yet settled and often confusing such as the vitreomacular traction (VMT) syndrome.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)